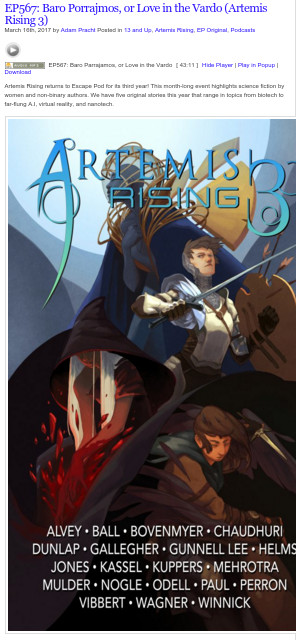

Today, my first fiction publication went live.

Today, my first fiction publication went live.

This story is a result of me putting in some real effort to learn more about my Romani grandmother. Because of how my brain works, these efforts produced a near-future dystopia.*

In “Love in the Vardo,” I attempted to tap into what little I know of the Gunnell/Lee line, which I think comes out in the details included about Shuri’s father, Anya’s sardonic humour, and Edingel Lee’s gentle authority. There is a lot of my family in this piece, though it is perhaps fairly well hidden to all but me.

Many hours of research went into Romani language and religious customs for this piece. For this I got a lot of information from essays in the book Gypsy Law: Romani Legal Traditions and Culture—specifically from Dr. Ian Hancock’s contributions.

There are a few tropes I play with in this story—tropes which any Romani person would immediately recognize, but someone outside of the culture would probably accept as rote. The first (and probably most offensive) is the idea of the “dirty gypsy”. In the book We Are the Romani People, Ian Hancock writes about this trope. Even though hygiene is extremely important in Romani culture, often poverty and outright persecution resulted in reduced access to running water and other resources:

Given equal access to the normal amenities, we are a people who are fastidious about personal cleanliness and hygiene. The time spent in the concentration camps during the Porrajmos was unbearable for our people, as it is today in refugee centres, where little or no provision is made for maintaining strict hygiene or for preparing food in a ritually clean way.

Shuri’s memories of her father are very much rooted in memories of my own father. I grew up in a working class family, which meant that my father worked outside the house and also did a lot of his own maintenance and construction at home. My sister especially helped him with home renovations. I remember him being very eager to try to fix anything, sometimes more successfully than others. But, of course, he always washed up afterwards, just as Shuri’s father does.

Another trope in the story is that of the wandering gypsy—a person who just cannot settle down, must keep travelling, whose “home is the open road”. It is true that travelling is a part of Romani history, but the other side of this coin is that much travelling is done because of local legislation which results in evictions or being forced to keep moving through towns and cities. Other travelling is done to find work. The romantic idea of the restless soul is, in reality, overshadowed by practicalities. In this story, Shuri’s people keep moving in response to their former captivity.

This story was never meant to be an accurate depiction of the lives of present-day Roma—rather an extrapolation of future Romani culture after continuous fracturing akin to what many communities have already experienced. I do try to be true to present realities in my future conjectures.

If you do listen to it, let me know what you think.

*In the midst of my research for this story, I also read Joanna Russ’ “When It Changed” (1972) for the first time. To say I was quite taken with this story would probably be an understatement. It is definitely peeking through “Love in the Vardo”.